What drives conflict-related sexual violence?

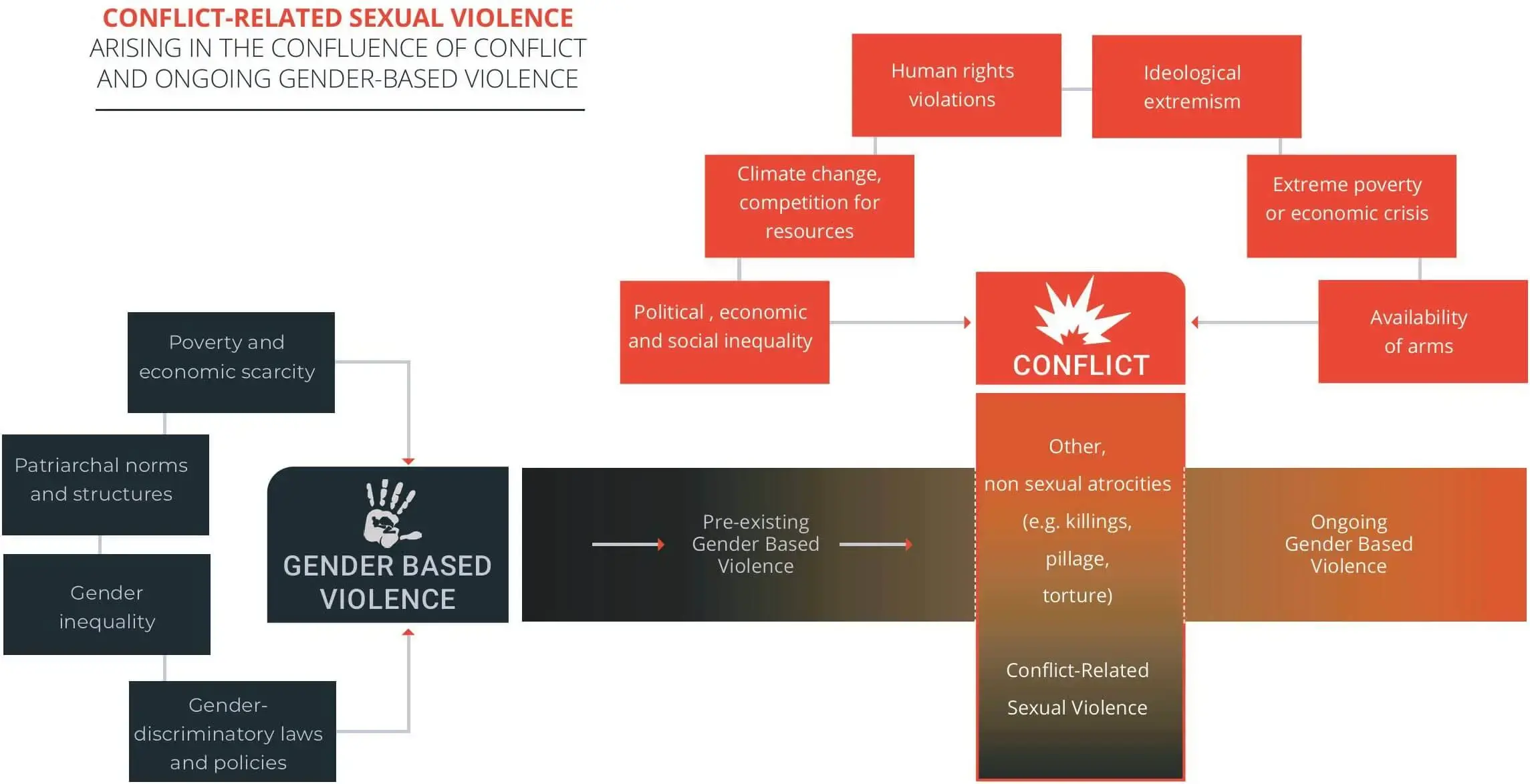

Conflict-related sexual violence is a form of both gender-based violence and violent conflict. Occurring at the confluence of the two, it has multiple root causes associated with both. These often intersect, creating distinct, compounding risks. For example, misogynistic extremist ideologies might combine with access to weapons and the destruction of social support networks. The risk factors for conflict-related sexual violence can accelerate its speed and/or severity and may increase the likelihood of it happening repeatedly.

Protection and prevention of conflict-related sexual violence require understanding the drivers and how they may interact, including to reach the most vulnerable or at-risk populations or areas. Responding also calls for a survivor-centred approach that puts survivors’ needs, wants and dignity at the heart of every activity.

We must dig deeper and unearth the intertwined root causes of conflict-related sexual violence, and in their place sow the seeds of prevention and change.

Drivers related to conflict

Drivers of armed conflict that may influence the risks of conflict-related sexual violence include:

- Political, economic, and social inequalities

- Human rights violations

- Tensions between different groups or a lack of social cohesion

- Extreme poverty or economic crisis

- Climate change and environmental degradation, and competition for natural resources

- Ideological extremism

- Criminal networks or generalized violence

- The availability of arms

- Absence of the rule of law

- Forced displacement

Drivers of gender-based violence

Gender-based violence is caused by gender discrimination and power imbalances. The RESPECT framework defines four categories of risks and examples of how they manifest. Any or all of these may be present in conflict situations:

Societal

- Discriminatory laws on property ownership, marriage, divorce, and child custody

- Low levels of women’s employment and education

- Absence or lack of enforcement of laws addressing violence against women

- Gender discrimination in institutions

Community

- Harmful gender norms that uphold male privilege and limit women’s autonomy

- High levels of poverty and unemployment

- High rates of violence and crime

- Availability of drugs, alcohol, and weapons

Interpersonal

- High levels of inequality in relationships/male-controlled relationships/dependence on partner

- Men’s multiple sexual relationships

- Men’s use of drugs and harmful use of alcohol

Individual

- Childhood experience of violence and/or exposure to violence in the family

- Mental disorders

- Attitudes condoning or justifying violence as normal or acceptable

Risks are determined by who people are

Risks of conflict-related sexual violence may be specific or higher for certain groups. For example:

- Women and girls of childbearing age may be targeted for reproductive harms, such as forced pregnancy, forced sterilization, and forced marriage.

- Detainees may be sexually tortured during interrogations or forced to perform sexual acts for food or safety.

- Persons with diverse sexual orientations, gender identities, gender expressions, and sex characteristics may be singled out for sexual violence or “social cleansing”.

- Children and young people recruited by armed groups or terrorist organizations may become victims, perpetrators, or both.

Other groups facing distinct risks are those of an actual or presumed race, ethnicity, political opinion, or relationship to enemy fighters.

Circumstances also matter

Being displaced, in detention, or in an occupied community are all situations that can amplify risks of conflict-related sexual violence.

Perpetrators may deliberately target women with high public visibility, such as community leaders, human rights defenders, or political activists.

Survivor-centred and intersectional approaches

The Inter-Agency Standing Committee defines a survivor-centred approach as an one that “places the rights, wishes, needs, safety, dignity and well-being of the victim/survivor at the centre of all prevention and response measures”.

An intersectional approach sheds light on how multiple aspects of the identity or position of a person or community may result in compounding risks of conflict-related sexual violence. For instance:

- Forced pregnancy or forced abortion may be perpetrated against women of a specific ethnic group as part of ethnic cleansing.

- Armed actors may target rural Indigenous women associated with the political opposition.

- Areas with the worst insecurity may be home to poor rural women with limited access to police and other services, much less the political clout to demand them.

Any activity responding to or preventing conflict-related sexual violence requires a principled approach that considers the needs of the survivor above all else. This often means tailoring a response based on recognizing the unique identity of the survivor, including their strengths, vulnerabilities, and contextual positioning.

A survivor-centred, intersectional approach is the most effective way to stop the cycle of violence. It addresses compounding forms of oppression that may heighten the invisibility or stigmatization of conflict-related sexual violence, which in turn makes protection and prevention more difficult and impedes access to justice.

The greatest form of protection: Ending gender inequality

Greater gender equality—political, social, and economic—cuts the risks of war, according to growing evidence. Some research suggests that women’s security is one of the most reliable indicators of the peacefulness of a State.

Increasing gender equality and upholding women’s rights can reduce vulnerability to the risks of conflict-related sexual violence. It can also improve individuals’ abilities to protect themselves or seek safety.

Examples include:

- Laws guaranteeing equal rights and prohibiting gender-based discrimination

- Judicial services that are accessible and tailored to the specific needs of women victims/survivors

- Women’s increased participation and leadership in peace processes and political decision-making

- Equitable opportunities for women across the economy

- Socialization promoting gender-equitable norms, including around decision-making

Programmes to achieve the systemic, structural changes that gender equality requires have a longer timeframe. But their intent can be applied even in shorter-term conflict response or recovery efforts.

One study from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, for instance, found that economic empowerment programmes had a greater impact on the well-being of survivors of sexual violence compared to other women.